Could you forgive your son if he got behind the wheel while high and killed a beloved teacher?

A Hit-and-Run

On May 25, 2016, in Santa Clarita, California, 28-year-old Lucas Guidroz got into his car while high on heroin and hit and killed a bicyclist. He fled from the scene of the crime, abandoning his vehicle. Roderick Bennett was 53 years old when he died on that road, and his wife Valerie was left “in a fog without him.” Roderick was a beloved math teacher and band director.

Within a couple days, Lucas turned himself in, and the Guidroz family found themselves faced with a tragedy they couldn’t wrap their heads around. On November 7, 2016, teary-eyed Lucas listened as the judge sentenced him to ten years in state prison for “gross vehicular manslaughter while intoxicated, and hit-and-run driving resulting in death.”

How does a family navigate that?

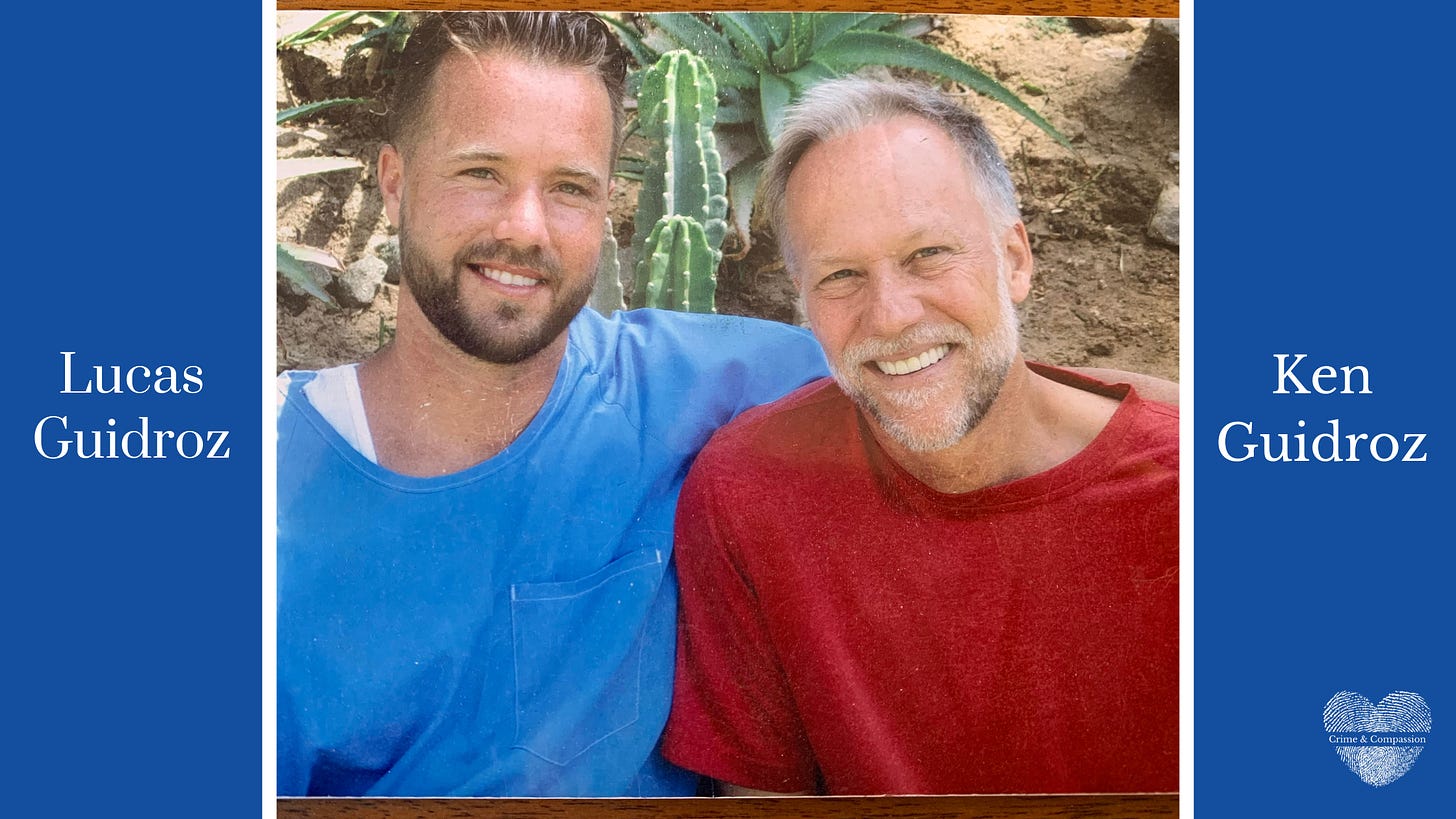

Faced with the challenge of his son’s incarceration, Ken Guidroz embarked on a last-ditch effort to connect with Lucas by writing letters. And . . . it worked. It led to a transformative change in their relationship over several years. The profound impact of this experience inspired Ken to share his journey in his award-winning book, Letters to My Son in Prison.

Ken and I discuss the crime, its aftermath, and his sheer willingness to help his son, and to love and forgive him.

Don’t forget to subscribe to the Crime & Compassion Substack (it’s free), or you can become a paid member to support this cause.

The True Story

Embark on a raw and gripping journey as Ken confronts his son's incarceration, sharing about parenting demons, marriage resilience, and spiritual rediscovery.

The reader gets to witness this father of three grapple with self-doubt, questioning his abilities as a father. What did I do wrong? Later he creatively uses letters to reconnect with his estranged son, leading to the development of an entirely new relationship.

After being married for almost 40 years, he asked himself: How are we going to survive this? Ken recounts some of the strained conversations he and his wife had as they coped with the challenges of this crisis.

Having once served as a pastor, doubts about his faith haunted him, leading him to question God: How could God allow this in my family? The spiritual insights he gained were not superficial or clichéd. These realizations were forged through genuine struggle and refining fire.

I did not want my son to move back home.

Lucas had hit another rough patch. He’d lost another job, gotten kicked out of his girlfriend’s apartment, and was ghosting his AA sponsor. Now he needed a place to stay, so the texts to his mother started dinging like the service bell at lunchtime at Jerry’s Deli. He was twenty-seven.

“Nope, I don’t think we should let him move back in,” I told my wife, Joyce. Then her phone dinged again.

Ha! He sure ain’t gonna text me, I thought. He remembers my little ditty:

“No mon, no fun, your son. How sad, too bad, your dad.”

I knew how this move back home would unfold. He’d play the game for a few days—get up on time, help around the house, and look for a job—but soon enough his bedroom door would be closed until ten in the morning, and the knobs on his video controller would be rubbed to a shine. Then the crumbs would appear—oh, those crumbs. I’d see them on the white-tiled kitchen counter—crumbs that a normal, sober, trying-to-go-unnoticed, trying-not-to-get-kicked-out-of-your-parents’-home young man would never leave so mockingly visible.

Joyce, with her mama bear in full swing, said, “I know…it’s not perfect. But what’s he gonna do? Where’s he gonna stay?”

I thought, It’s not our job to figure out where our twenty-seven-year-old son stays.

Then, as if she’d read my mind, she said, “What if we lay things out super clear? Like when he has to be home and has to have a job by, and that we’ll do random drug tests.”

“And I become the bad cop?” I whined. “No way. I can’t do that again, honey. I’m the one stuck here all day and you get to go to your job at school. I’m the one who’s gonna see his slide. I’m the one who’s gonna hear those ridiculous excuses. And I’m the one who’s gonna have to endure those wretched crumbs on the counter.”

Joyce ran her fingers over the worn grooves of our distressed-oak kitchen table.

“If we’re not careful,” I said softly, “he’s gonna drag us down with him.”

Even as I said it, though, I knew that “us” was not the real concern here. Joyce wasn’t concerned about “us” and, honestly, neither was I. In thirty-plus years of marriage, we had never uttered the D-word, or even contemplated it. But this was a new level. Losing a son to opioids tested us like nothing ever had. We’d started doubting each other, snapping at each other, and misreading intentions. She’d lend him some money and I’d say, “You’re enabling.” I’d turn away from a need and she’d say, “You’re too removed.”

Without lifting her eyes from the table, she murmured, “I hear you, I really do. But we just can’t—well, I can’t—abandon him right now.”

I whispered, “Honey, I don’t think I can do this again.”

She looked outside to our patio, and said, “But…where will he sleep?”

“It’s not our job to figure out where he sleeps,” I said meekly. “He does have wheels.”

She spun toward me. “You want him sleeping in his car?”

“That’s not what I said…” I pulled in my breath, not wanting to launch. What I really wanted to say was, How did this become about me wanting him to sleep in his car? But after a moment of chewing on my tongue, I just murmured, “What I meant was that at least he can get around.”

As I thought about my car comment, though, she was actually dead-on. I was suggesting he could sleep in his car. But I decided to keep that little thought to myself.

Joyce stared at the table and said, “Not yet.”

I waited.

“I’m not ready to cut him off,” she said softly, but with conviction.

“Joyce—”

She looked up at me from the table and said, “I just couldn’t live with myself if something happened to him.”

That was it. That was all she needed to say. “I just couldn’t live with myself,” in that moment, was our version of a safe word. It stopped the conversation cold. And it’s not like we had ever talked about this phrase or agreed to it as holy, but as soon as it was uttered, it was as immutable as a wedding vow. My thinking was that if Joyce couldn’t live with herself because something happened to him, even if it was his own fault, after I’d forced the issue, then she might struggle living with me, or worse, not be able to live with me. And, after all we’d been through, not only with Lucas but with both our other two sons, I couldn’t live with myself if something happened to us. I needed there to be an us. No matter the cost, no matter the pride-swallowing, no matter the concessions I might need to make, there needed to be an us.

Do other couples have a phrase like this? Do they have moments like these? I don’t know. But when it happened to us, I knew it was huge. I could sense it. I felt unsteady, because after all these years of parenting, my confidence had come to an all-time low and I was mostly deferring to Joyce anyway. For the first half of my parenting life, I thought I had the gift; I thought I had the parenting gene. Handling my three boys felt as intuitive as riding a bike. But over the past fifteen years, I’d lost my mojo and felt like I was wobbling all over the road, bumping into things, and getting flat tires. My little dad gene had turned into a dad meme.

I said, “Okay, he can move back in.” And when I said it, I didn’t feel chastened or humiliated or put in my place. I simply accepted her words for what they were. I said, “I’ll talk to him about moving back home.”

Well, I did. He moved back home. And, as we expected, he slipped into old patterns—missing job interviews, sleeping in, abusing substances, forcing us to kick him out again.

About a year later, while living with his girlfriend, he was trying for the umpteenth time to get on his feet. Driving home after work one day, on a country road just outside of town, fighting off the overwhelming fatigue of a five-day heroin bender, he veered onto the thin shoulder of the road, where a man was on an afternoon bike ride. The cyclist never knew what hit him. One minute, he was navigating his front tire between the gravel shoulder and a solid white line. The next, darkness.

This is the story of what became of Lucas while he was in prison.

It’s also the story of what became of me and Lucas while he was in prison, along with the unexpected role that letters played in that evolution. By the time he was incarcerated, we were out of communication options. Face-to-face was only allowed in a visiting room, talking on phones through thick glass, with what felt like the heavy cloud of ten years of disappointment hanging over us. And phone calls weren’t much better. They were maxed at fifteen minutes and reverberated with inmates screaming in the background. Letters seemed to be the only option left.

This is also the story of what became of me and Joyce while he was in prison.

In the end, though, it’s the story of what became of me. Not only as a dad and a husband, but also as a man whose faith was shaken by what happened. I had spent thirty years involved in a close-knit church, many of them as a leader, and I thought things would work out differently for me and my family. I thought God would bless us. So to have my family implode like it did struck at the core of my faith and made me feel like a spiritual failure, about as far away from God as I could be.

It is also the story of how I came to see my old church as part of the problem. I realized that people had become too prominent and God too small; religion had become too important and the Spirit too trivial. Instead of listening to God’s voice inside of me, I cowered to the Bible-thumping strongman. I let him intimidate me. I let him guilt me. And I let him influence me to become the dad I never wanted to be.

Through this experience, I needed to find out if God was the God of the strongman. I needed to see if I could hear the Spirit’s voice again. And I needed to see that God was available to imperfect fathers and imperfect families and prodigals of all kinds—whether that prodigal be a son who lost himself to opioids, or to a father who lost his way with his family and with his God.

On a Personal Note

In January 2023, I made the announcement that I was changing my career. In the newsletter I had sent out, I talked about Crime & Compassion and its mission and the long journey I had before me to make C&C a reality.

I received a reply to that newsletter: a man named Ken Guidroz wanted to tell me about his then-upcoming book and how he’d like to support my mission.

I knew immediately that I had to interview him.

Here was a father whose son had committed vehicular manslaughter, yet Ken forgave him, loved him, helped him, prayed for and with him. But, but, but: It was also Ken’s raw honesty that truly struck my heart, that took my breath away.

Ken didn’t have to talk about his anger toward his son, toward God, toward himself. Ken didn’t have to talk about his own shortcomings, his marriage, his spiritual struggle. Ken didn’t have to be “so honest,” if you will. But he told this story with candor and humility, and I’ll never forget that.

And to Lucas, if you’re reading this: I am so ridiculously proud of you. I can’t imagine all the different emotions you’ve combated over the years. I can’t imagine how difficult things must’ve been. I certainly can’t imagine the fight it took to get to where you are today. I am in awe of you! Something terrible happened; something beautiful happened too. (And if you’d ever like to be on the show, I’d be honored to have you.)

Finally, to Ken: I hope you truly, truly understand that this entire story can and will change perspectives, change hearts, and change lives.

Your Bleeding Heart,

Shayla Hale

Get to Know Ken

Ken Guidroz is a former pastor with over two decades of experience in designing specialty retirement plans for companies. In 2010, he co-authored the definitive guide on these plans, titled Beyond the 401(k).

In 2016, faced with the challenge of his son's incarceration, Ken embarked on a last-ditch effort to connect with him by writing letters. Remarkably, this endeavor proved successful, leading to a transformative change in their relationship over several years. The profound impact of this experience inspired Ken to share his journey in the book titled Letters to My Son in Prison. Within its pages, he recounts the evolution of their connection, delves into the challenges he and his wife overcame, and explores his rediscovery of spirituality beyond the confines of traditional religion.

Currently residing in Santa Clarita, CA, Ken shares his life with his wife of over forty years. Their three sons and their families live nearby. Ken continues to contribute his expertise to the field of retirement planning, working for FuturePlan in the ongoing design of retirement plans.

Crime & Compassion strives to shake up how we view and treat the incarcerated. Podcast host Shayla Hale asks difficult questions to gain a more compassionate understanding of those who were written off. The podcast serves as a safe space for the formerly incarcerated, currently incarcerated, their families and loved ones, and those who work with men and women in US jails and prisons. Crime & Compassion’s goals are 1) to show love and kindness toward the captives, 2) to help bring their stories and art into the world, 3) to completely flip the narrative on the US justice system by having tough conversations, 4) to educate society on why people commit the crimes they do, and 5) to reframe how people see, treat, and think about the incarcerated.

Share this post